Issue 174, Summer 2005

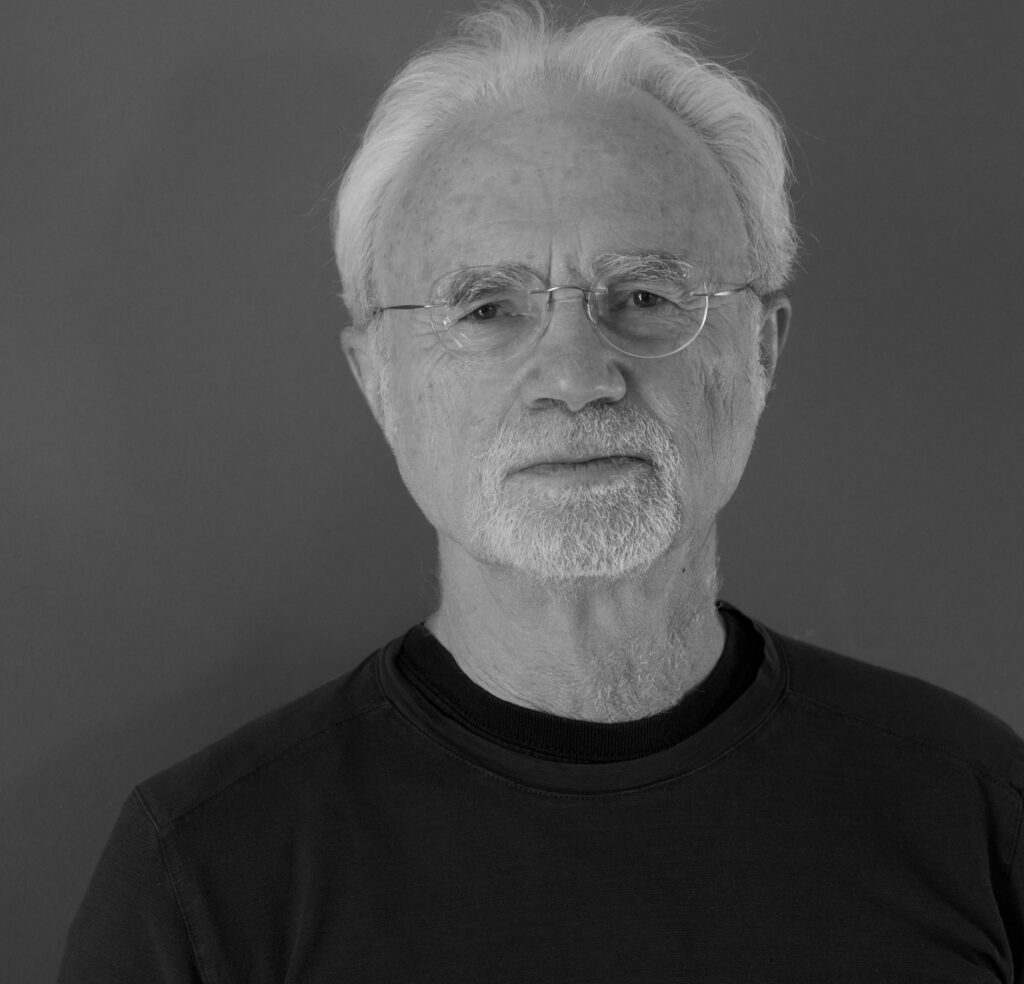

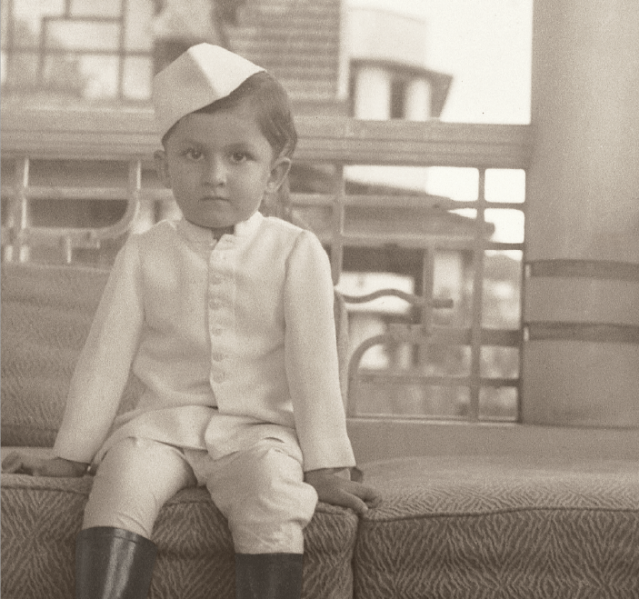

Salman Rushdie as a boy in Bombay.

Salman Rushdie as a boy in Bombay.

Salman Rushdie was born in Bombay in 1947, on the eve of India’s independence. He was educated there and in England, where he spent the first decades of his writing life. These days Rushdie lives primarily in New York, where this interview was conducted in several sessions over the past year. By coincidence, the second conversation took place on Valentine’s Day 2005, the sixteenth anniversary of the Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Rushdie, which proclaimed him an apostate for writing The Satanic Verses and sentenced him to death under Islamic law. In 1998, Iran’s president, Mohammed Khatami, denounced the fatwa, and Rushdie now insists that the danger has passed. But Islamic hardliners regard fatwas as irrevocable and Rushdie’s home address remains unlisted.

For a man who occasioned such furor, who has been lauded and blamed, threatened and feted, burnt in effigy and upheld as an icon of free expression, Rushdie is surprisingly easygoing and candid—neither a hunted victim nor a scourge. Clean shaven, dressed in jeans and a sweater, he actually looks like a younger version of the condemned man who stared out at his accusers in Richard Avedon’s famous 1995 portrait. “My family can’t stand that picture,” he said, laughing. Then, asked where the photograph is stored, he grinned and replied, “On the wall.”

When he is working, Rushdie said, “it is rather unusual of me to come out in the daytime.” But late last year he handed in the manuscript for Shalimar the Clown, his ninth novel, and he has not yet started a new project. Although he claimed he’d exhausted his resources finishing the book, he seemed to gain energy as he talked about his past, his writing, his politics. In conversation, Rushdie performs the same mental acrobatics that one finds in his fiction—snaking digressions that can touch down on several continents and historical eras before returning to the original point.

The fatwa ensured that the name Salman Rushdie is better known around the world than that of any other living novelist. But his reputation as a writer has hardly been eclipsed by the political assaults. In 1993, he was awarded the “Booker of Bookers”—a medal honoring his novel Midnight’s Children as the best book to win the Man Booker Prize since it was established twenty-five years earlier—and he is currently the president of the PEN-American Center. In addition to his novels, he is the author of five volumes of nonfiction, and a short-story collection. On Valentine’s Day, as he arranged himself in a padded chair, a light snow fell, and the incinerator stack of a building a few blocks east blew a column of black smoke into the sky. Rushdie drank from a glass of water and talked about finding his wife the right gift before settling into questions.

INTERVIEWER

When you’re writing, do you think at all about who will be reading you?

SALMAN RUSHDIE

I don’t really know. When I was young, I used to say, No, I’m just the servant of the work.

INTERVIEWER

That’s noble.

RUSHDIE

Excessively noble. I’ve gotten more interested in clarity as a virtue, less interested in the virtues of difficulty. And I suppose that means I do have a clearer sense of how people read, which is, I suppose, partly created by my knowledge of how people have read what I have written so far. I don’t like books that play to the gallery, but I’ve become more concerned with telling a story as clearly and engagingly as I can. Then again, that’s what I thought at the beginning, when I wrote Midnight’s Children. I thought it odd that storytelling and literature seemed to have come to a parting of the ways. It seemed unnecessary for the separation to have taken place. A story doesn’t have to be simple, it doesn’t have to be one-dimensional but, especially if it’s multidimensional, you need to find the clearest, most engaging way of telling it.

One of the things that has become, to me, more evidently my subject is the way in which the stories of anywhere are also the stories of everywhere else. To an extent, I already knew that because Bombay, where I grew up, was a city in which the West was totally mixed up with the East. The accidents of my life have given me the ability to make stories in which different parts of the world are brought together, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in conflict, and sometimes both—usually both. The difficulty in these stories is that if you write about everywhere you can end up writing about nowhere. It’s a problem that the writer writing about a single place does not have to face. Those writers face other problems, but the thing that a Faulkner or a Welty has—a patch of the earth that they know so profoundly and belong to so totally that they can excavate it all their lives and not exhaust it—I admire that, but it’s not what I do.

INTERVIEWER

How would you describe what you do?

RUSHDIE

My life has given me this other subject: worlds in collision. How do you make people see that everyone’s story is now a part of everyone else’s story? It’s one thing to say it, but how can you make a reader feel that is their lived experience? The last three novels have been attempts to find answers to those questions: The Ground Beneath Her Feet and Fury and the new one, Shalimar the Clown, which begins and ends in L.A., but the middle of it is in Kashmir, and some is in Nazi-occupied Strasbourg, and some in 1960s England. In Shalimar, the character Max Ophuls is a resistance hero during World War II. The resistance, which we think of as heroic, was what we would now call an insurgency in a time of occupation. Now we live in a time when there are other insurgencies that we don’t call heroic—that we call terrorist. I didn’t want to make moral judgments. I wanted to say: That happened then, this is happening now, this story includes both those things, just look how they sit together. I don’t think it’s for the novelist to say, It means this.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have to restrain yourself from saying, It means this?

RUSHDIE

No. I’m against that in a novel. If I’m writing an op-ed piece, it’s different. But I believe that you damage the novel by instructing the reader. The character of Shalimar, for example, is a vicious murderer. You’re terrified of him, but at certain points—like the scene where he flies off the wall in San Quentin—you’re rooting for him. I wanted that to happen, I wanted people to see as he sees, to feel as he feels, rather than to assume they know what kind of man he is. Of all my books this was the book that was most completely written by its characters. Quite a lot of the original conception of the book had to be jettisoned because the characters wanted to go another way.

INTERVIEWER

What do you mean?

RUSHDIE

Moment by moment in the writing, things would happen that I hadn’t foreseen. Something strange happened with this book. I felt completely possessed by these people, to the extent that I found myself crying over my own characters. There’s a moment in the book where Boonyi’s father, the pandit Pyarelal, dies in his fruit orchard. I couldn’t bear it. I found myself sitting at my desk weeping. I thought, What am I doing? This is somebody I’ve made up. Then there was a moment when I was writing about the destruction of the Kashmiri village. I absolutely couldn’t bear the idea of writing it. I would sit at my desk and think, I can’t write these sentences. Many writers who have had to deal with the subject of atrocity can’t face it head-on. I’ve never felt that I couldn’t bear the idea of telling a story—that it’s so awful, I don’t want to tell it, can something else happen? And then you think, Oh, nothing else can happen, that’s what happens.

INTERVIEWER

Kashmir is family territory for you.

RUSHDIE

My family’s from Kashmir originally, and until now I’ve never really taken it on. The beginning of Midnight’s Children is in Kashmir, and Haroun and the Sea of Stories is a fairy tale of Kashmir, but in my fiction I’ve never really addressed Kashmir itself. The year of the real explosion in Kashmir, 1989, was also the year in which there was an explosion in my life. So I got distracted, and . . . By the way, today is the anniversary of the fatwa. Valentine’s Day is not my favorite day of the year, which really annoys my wife. Anyway, Shalimar was a kind of attempt to write a Kashmiri Paradise Lost. Only Paradise Lost is about the fall of man—paradise is still there, it’s just that we get kicked out of it. Shalimar is about the smashing of paradise. It’s as if Adam went back with bombs and blew the place up.

I’ve never seen anywhere in the world as beautiful as Kashmir. It has something to do with the fact that the valley is very small and the mountains are very big, so you have this miniature countryside surrounded by the Himalayas, and it’s just spectacular. And it’s true, the people are very beautiful too. Kashmir is quite prosperous. The soil is very rich, so the crops are plentiful. It’s lush, not like much of India, in which there’s great scarcity. But of course all that’s gone now, and there is great hardship.

The main industry of Kashmir was tourism. Not foreign tourism, Indian tourism. If you look at Indian movies, every time they wanted an exotic locale, they would have a dance number in Kashmir. Kashmir was India’s fairyland. Indians went there because in a hot country you go to a cold place. People would be entranced by the sight of snow. You’d see people at the airport where there’s dirty, slushy snow piled up by the sides of the roads, standing there as if they’d found a diamond mine. It had that feeling of an enchanted space. That’s all gone now, and even if there’s a peace treaty tomorrow it’s not coming back, because the thing that was smashed, which is what I tried to write about, is the tolerant, mingled culture of Kashmir. After the way the Hindus were driven out, and the way the Muslims have been radicalized and tormented, you can’t put it back together again. I wanted to say: It’s not just a story about mountain people five or six thousand miles away. It’s our story, too.

INTERVIEWER

We’re all implicated in it?

RUSHDIE

I wanted to make sure in this book that the story was personal, not political. I wanted people to read it and form intimate, novelistic attachments to the characters and if I did it right it won’t feel didactic, and you’ll care about everybody. I wanted to write a book with no minor characters.