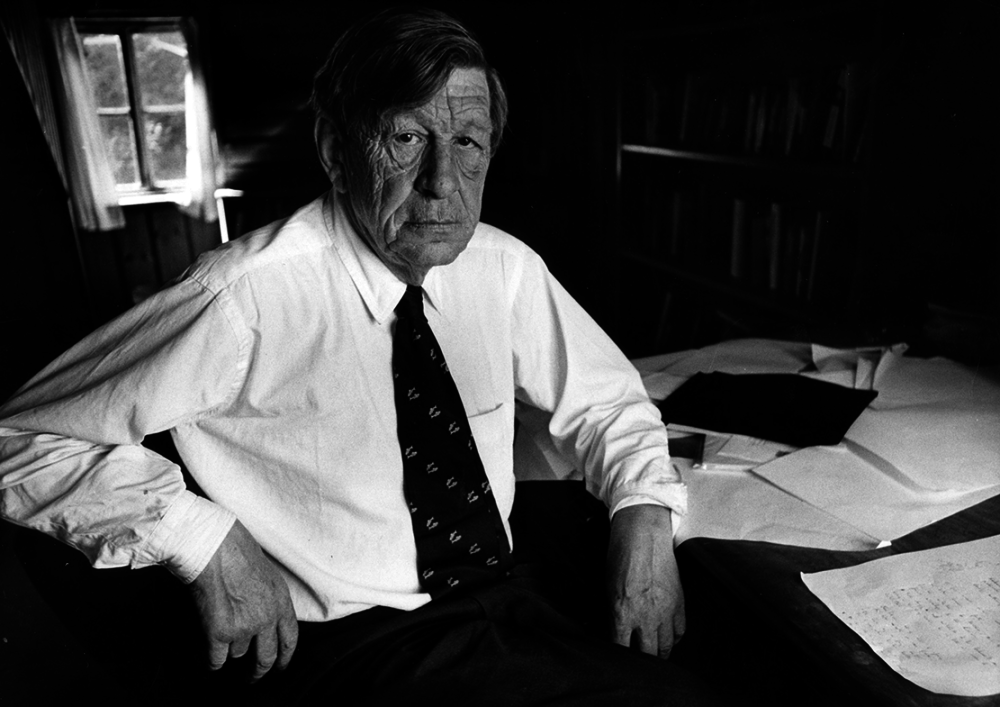

Issue 57, Spring 1974

AUDEN

What’s that again?

INTERVIEWER

I wondered which living writer you would say has served as the prime protector of the integrity of our English tongue . . . ?

AUDEN

Why, me, of course!

—Conversation, Autumn 1972

He was sitting beneath two direct white lights of a plywood portico, drinking a large cup of strong breakfast coffee, chain-smoking cigarettes, and doing the crossword puzzle that appears on the daily book review page of The New York Times—which, as it happened, this day contained, along with his photo, a review of his most recent volume of poetry.

When he had completed the puzzle, he unfolded the paper, glanced at the obits, and went to make toast.

Asked if he had read the review, Auden replied: “Of course not. Obviously these things are not meant for me . . .”

His singular perspectives, priorities, and tastes were strongly manifest in the décor of his New York apartment, which he used in the winter. Its three large, high-ceilinged main rooms were painted dark gray, pale green, and purple. On the wall hung drawings of friends—Elizabeth Bishop, E. M. Forster, Paul Valéry, Chester Kallman—framed simply in gold. There was also an original Blake watercolor, The Act of Creation, in the dining room, as well as several line drawings of male nudes. On the floor of his bedroom, a portrait of himself, unframed, faced the wall.

The cavernous front living room, piled high with books, was left dark except during his brief excursions into its many boxes of manuscripts or for consultations with the Oxford English Dictionary.

Auden’s kitchen was long and narrow, with many pots and pans hanging on the wall. He preferred such delicacies as tongue, tripe, brains, and Polish sausage, ascribing the eating of beefsteak to the lower orders (“it’s madly non-U!”). He drank Smirnoff martinis, red wine, and cognac, shunned pot, and confessed to having, under a doctor’s supervision, tried LSD: “Nothing much happened, but I did get the distinct impression that some birds were trying to communicate with me.”

His conversation was droll, intelligent, and courtly, a sort of humanistic global gossip, disinterested in the machinations of ambition, less interested in concrete poetry, absolutely exclusive of electronic influence.

As he once put it: “I just got back from Canada, where I had a run-in with McLuhan. I won.”

INTERVIEWER

You’ve insisted we do this conversation without a tape recorder. Why?

W. H. AUDEN

Because I think if there’s anything worth retaining, the reporter ought to be able to remember it. Truman Capote tells the story of the reporter whose machine broke down halfway into an interview. Truman waited while the man tried in vain to fix it and finally asked if he could continue. The reporter said not to bother—he wasn’t used to listening to what his subjects said!

INTERVIEWER

I thought your objection might have been to the instrument itself. You have written a new poem condemning the camera as an infernal machine.

AUDEN

Yes, it creates sorrow. Normally, when one passes someone on the street who is in pain, one either tries to help him, or one simply looks the other way. With a photo there’s no human decision; you’re not there; you can’t turn away; you simply gape. It’s a form of voyeurism. And I think close-ups are rude.

INTERVIEWER

Was there anything that you were particularly afraid of as a child? The dark, spiders, and so forth.

AUDEN

No, I wasn’t very scared. Spiders, certainly—but that’s different, a personal phobia which persists through life. Spiders and octopi. I was certainly never afraid of the dark.

INTERVIEWER

Were you a talkative child? I remember your describing somewhere the autistic quality of your private world.

AUDEN

Yes, I was talkative. Of course there were things in my private world that I couldn’t share with others. But I always had a few good friends.

INTERVIEWER

When did you start writing poetry?

AUDEN

I think my own case may be rather odd. I was going to be a mining engineer or a geologist. Between the ages of six and twelve, I spent many hours of my time constructing a highly elaborate private world of my own based on, first of all, a landscape, the limestone moors of the Pennines; and second, an industry—lead mining. Now I found in doing this, I had to make certain rules for myself. I could choose between two machines necessary to do a job, but they had to be real ones I could find in catalogues. I could decide between two ways of draining a mine, but I wasn’t allowed to use magical means. Then there came a day which later on, looking back, seems very important. I was planning my idea of the concentrating mill—you know, the platonic idea of what it should be. There were two kinds of machinery for separating the slime, one I thought more beautiful than the other, but the other one I knew to be more efficient. I felt myself faced with what I can only call a moral choice—it was my duty to take the second and more efficient one. Later, I realized, in constructing this world which was only inhabited by me, I was already beginning to learn how poetry is written. Then, my final decision, which seemed to be fairly fortuitous at the time, took place in 1922, in March when I was walking across a field with a friend of mine from school who later became a painter. He asked me, “Do you ever write poetry?” and I said, “No”—I’d never thought of doing so. He said: “Why don’t you?”—and at that point I decided that’s what I would do. Looking back, I conceived how the ground had been prepared.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of your reading as being an influence in your decision?

AUDEN

Well, up until then the only poetry I had read, as a child, were certain books of sick jokes—Belloc’s Cautionary Tales, Struwwelpeter by Hoffmann, and Harry Graham’s Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes. I had a favorite, which went like this:

Into the drinking well

The plumber built her

Aunt Maria fell;

We must buy a filter.

Of course I read a good deal about geology and lead mining. Sopwith’s A Visit to Alston Moor was one, Underground Life was another. I can’t remember who wrote it. I read all the books of Beatrix Potter and also Lewis Carroll. Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” I loved, and also Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines. And I got my start reading detective stories with Sherlock Holmes.

INTERVIEWER

Did you read much of Housman?

AUDEN

Yes, and later I knew him quite well. He told me a very funny story about Clarence Darrow. It seems that Darrow had written him a very laudatory letter, claiming to have saved several clients from the chair with quotes from Housman’s poetry. Shortly afterwards, Housman had a chance to meet Darrow. They had a very nice meeting, and Darrow produced the trial transcripts he had alluded to. “Sure enough,” Housman told me, “there were two of my poems—both misquoted!” These are the minor headaches a writer must live with. My pet peeve is people who send for autographs but omit putting in stamps.

INTERVIEWER

Did you meet Christopher Isherwood at school?

AUDEN

Yes, I’ve known him since I was eight and he was ten, because we were both in boarding school together at St. Edmund’s School, Hindhead, Surrey. We’ve known each other ever since. I always remember the first time I ever heard a remark which I decided was witty. I was walking with Mr. Isherwood on a Sunday walk—this was in Surrey—and Christopher said, “I think God must have been tired when He made this country.” That’s the first time I heard a remark that I thought was witty.